The Sahara is the largest desert in the world, excluding the Arctic and Antarctica. Described by its people as bahr bela ma, ‘the great sea without water’, it engulfs 9.2 million square kilometres of Northern and North-Western Africa, from the Mediterranean to the North Atlantic, and clear across to the Red Sea.

Once a lush, green landscape, its rapid desertification began 5-6,000 years ago, ascribed to the combined effects of grazing and browsing by domesticated livestock and the gradually changing orientation of the Earth’s rotational axis in relation to the Sun. As the fertile mountains withered into rocky plateaus and grassy woodlands were swallowed up by sand dunes, the tribal herdsmen and their flocks migrated south or coastwards to milder climes, and many wild species either perished or followed suit. Temperatures soared and rainfall dwindled.

But not all abandoned the Sahara. Through the heat haze, proud and indefatigable, came the Tuareg.

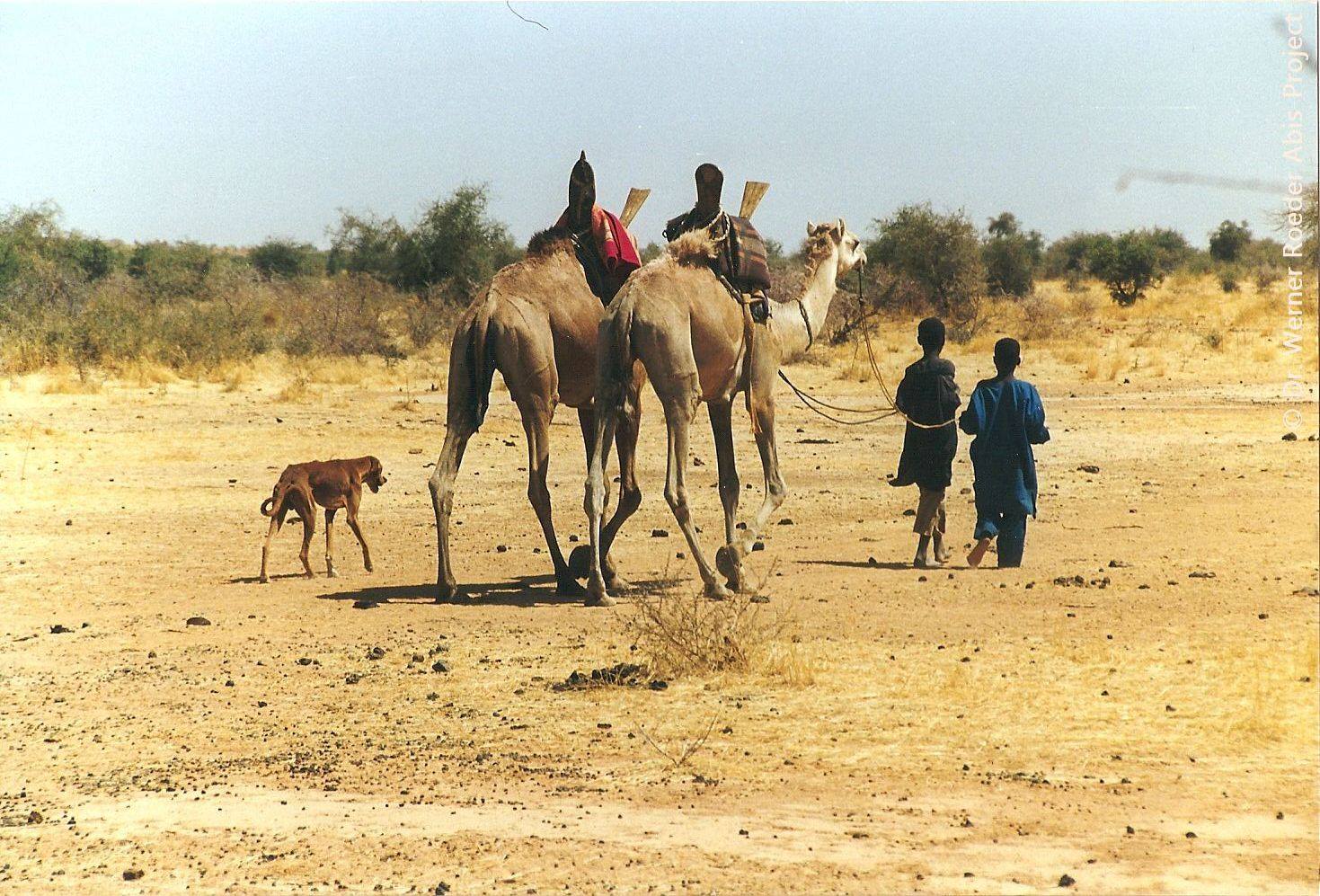

Descended from the Berber people (the Imazighen, ‘free men’) who have inhabited coastal North Africa for more than 50,000 years, the Tuareg refer to themselves as Kel Tamasheq, ‘people who speak [the] Tamasheq [language]’ … or sometimes, Kel Tagelmust, ‘veiled people’, referencing the head coverings traditionally worn by their men. Nomadic pastoralists, their ancestral lifestyle and inherent stoicism allowed them to become one with the shifting fortunes of the desert. Over generations, their unrivalled knowledge of its sparse oases, hidden wadis and accompanying feeding grounds earned them dominion over the pitiless landscape. They herded goats, sheep and cattle, and used dogs to assist in hunting desert game and to alert them to the approach of predators or thieves when they camped at night.

Initially, these dogs would have been the so-called ‘lupoid’ sighthounds, which archaeological evidence suggest existed in the Sahara as early as 4,500 years ago. Neolithic cave paintings throughout the region show these hounds as resembling larger Basenjis, with pricked ears and curled tails. It is not clear whether they evolved endemically from wild African canids (as did pariah dogs and ‘village dogs’ in other parts of the world) … or whether they were brought to Africa by much earlier migrations of people from the East. In either case, the lupoid sighthounds likely served as food for early Tuareg nomads as much as they did as hunting or guarding aids, as ancient Berbers habitually included dogs in their diet. However, over time, the Tuareg developed their own breed… far too valuable to be eaten.

The Tuareg were turning their unrivalled knowledge of the perilous routes across the Sahara to new advantage. Initially on horseback, and later with camels, they established lucrative trade routes transecting the desert, facilitating highly sought after commercial connections between northern and western coastal settlements, the African interior and the Middle East. Their trade routes were only viable due to the leaders’ relationships with many different clans of fellow Tuaregs located along the way, who granted them access to invaluable watering points and grazing pockets in exchange for supplies or other items of value. These rare refuges served as life-saving stepping stones across the increasingly barren desert. In return, the traders formed a conduit through which new ideas, knowledge, and other cultural developments could permeate the remote Tuareg society surprisingly quickly for the period.

Thus, when Phoenician colonisation of the Mediterranean coast introduced Middle Eastern and Indian coursing hounds to Northern Africa, it is logical to assume some of these dogs could have bred with Tuareg dogs when traders arrived at Northern coastal settlements – and may have been amongst the commodities sent west and south across the Sahara, breeding with local lupoid sighthounds during rest stops at Tuareg camps en route. Indeed, these types of hounds may have been traded directly from the fertile crescent along the Tuareg’s Saharan routes and mixed with the lupoid sighthounds in the process. As good quality hunting dogs they may have served as payment by Tuareg traders to local clan leaders for access to water and grazing. (Recent, although as yet, only small scale genetic testing of Azawakh in comparison to the Sloughis of Northern Africa, Salukis of the Middle East and Basenjis of the African interior seems to corroborate this hypothesis of Azawakh development).

Thus, the appearance of the Tuaregs’ dogs changed. Whilst Eastern dogs introduced dropped ears and longer tails, more open angulation and a higher tuck-up, the environment exacted its own influence. Similar adaptations can be seen in almost every mammal in the Sahara: longer legs to keep the body further from the hot ground, aided by an even higher tuck up; a shorter loin, narrower frame and flatter musculature to create a higher surface to volume ratio to reduce heat-retention; shorter guard-hair, absence of undercoat and thin skin to allow swifter heat-dissipation; and an elongated neck to keep the most valuable and temperature-sensitive organ, the brain, away from the heat of the body and even further from the hot ground.

The long neck also gives a periscopic view of the horizon – important for the hunter and the hunted alike – whilst the Azawakh’s almond-shaped eyes rimmed with black reduced glare. And as we already know from the more common sighthound breeds, a long nose and reduced stop is clearly advantageous to those who hunt by sight.

Efficiency of movement was another critical adaptation – that is, a precise physical design optimised to cover long distances whilst costing the least amount of metabolic effort and muscular and skeletal wear. This distinguishing movement set a good Azawakh apart from its competition, and still does today.

As the aridity of northern and western Africa continued to intensify, the Tuareg population were forced to restrict their nomadic pastoralist existence more and more to the southern edge of the Sahara, known as the Sahel. Meaning ‘shore’ in Arabic, the Sahel is a 200-300km wide transitional ecosystem between the true desert to the north and milder savannah to the south. The increasing harshness of this environment cemented the unique features of the Azawakh, as their Tuareg masters were fierce in selecting only the fittest, most functional individuals who could successfully survive alongside them without requiring undue care; aiding them in hunting gazelles, oryx, ostriches, hares and even lizards, and asking little in return.

Migration into the Sahel brought the Tuareg into closer contact with fellow nomadic pastoralists: the Fula (also called Peul in French or Fulani in Haussa); and also the Haussa, a more sedentary farming people. Fula and Haussa people saw great value in Azawakh both as hunting companions and guard dogs, and incorporated them into their communities. (Azawakh are also kept by Bellah people, also known as Ikelan, traditionally enslaved by the Tuareg and still struggling for independence in modern times).

French colonialism reached Africa in the 1800s, and restricted Tuareg movement even further, crushing much of their trans-Saharan trade and resisting their habit of crossing national borders in their nomadic pastoralist existence. The Tuareg retreated into the least habitable areas of the Sahel and southern Sahara, where they, their livestock and hounds could be left largely alone. Thus isolated, the Azawakh completed their transformation into a true landrace, strengthening their guarding instincts as resources grew scarcer and tribal tensions rose.

And there, a century later, in the Azaouagh basin, is where Europeans finally took notice of these remarkable dogs, and gave them their Western name. For in Africa, they are not called Azawakh, but Idi n’Illeli, ‘the sighthounds of the free people’.